Squat Mistakes When Training:

A Complete Guide to Injury Avoidance and Strength Gain

The Complete Guide to Squatting Safely — Benefits, Risks, and How to Get It Right

Introduction

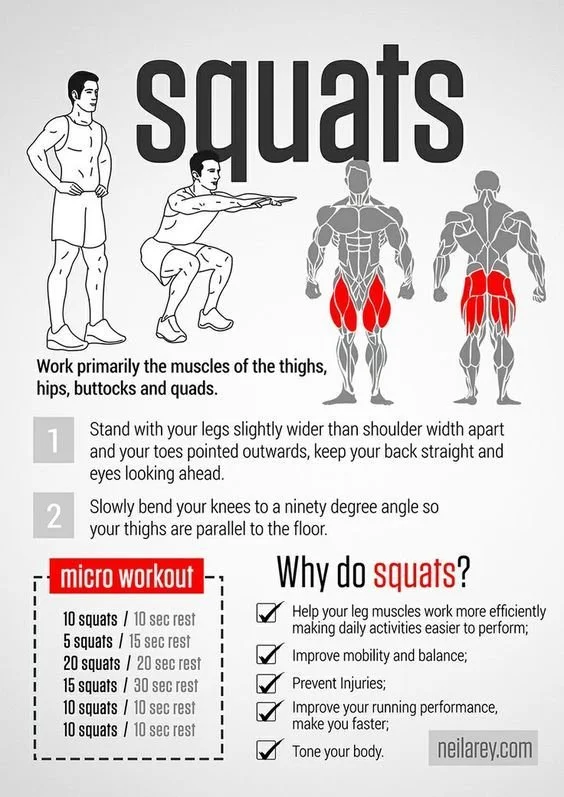

The squat has long been called the “king of exercises” — and for good reason. Performed with solid technique, it builds exceptional lower-body strength, supports bone density, enhances athletic performance, and reinforces fundamental movement patterns we use every day. Whether you train in Leeds, Bristol, or anywhere else in the UK, mastering the squat is one of the best investments you can make in your long-term strength and health.

However, the squat is also technically demanding. Poor form, mobility restrictions, rushed progression, or excessive loading can all raise the risk of injury. This guide explores what the research says about squatting, the real benefits of getting it right, and the most common mistakes that can hold you back or get you hurt.

Understanding Squat Injury Risk: What the Research Says

Despite its reputation, the squat is not inherently dangerous. In strength sports in general, injury rates are relatively modest when training is well-planned and technique is prioritised. Reviews of resistance training and strength sports show that the lower back, shoulder and knee are the most frequently injured regions, with muscle strains, tendinopathy and joint irritation being common. PubMed

Biomechanical work on the squat shows that changes in trunk angle, stance width, depth, knee travel and bar position all meaningfully alter how load is distributed through the hips, knees, ankles and lumbar spine. Small technical differences can greatly influence joint stress. PubMed PubMed

In elite powerlifters, one study found that athletes using front squats more frequently tended to report more knee and thigh issues, likely due to the more upright torso and greater forward knee travel that front squats demand. PubMed

Across multiple studies, common contributors to injury include:

Excessive loads relative to capacity

Large ranges of motion without sufficient control

Inadequate rest between heavy sessions

Fatigue leading to technique breakdown

Poor movement quality or unresolved mobility restrictions

Most injuries do not require full withdrawal from training; they are often manageable with modifications to load, volume or exercise selection. PubMed

The key message is simple: the squat is not the enemy — poorly performed, poorly programmed squatting is.

Why Squatting Is Worth It: Real Benefits of Proper Form

When you execute the squat correctly and progress it sensibly, the benefits are substantial and well supported by research.

Improved Bone Density

Heavy, weight-bearing resistance training stimulates bone remodeling and helps maintain or increase bone mineral density (BMD). In postmenopausal women with low bone mass, 12 weeks of maximal strength training with heavy squats led to increases in bone mineral content at the lumbar spine and femoral neck, alongside large gains in one-rep max strength and rate of force development. PubMed

In young men, a 24-week programme including squats and deadlifts produced significant increases in BMD, highlighting how heavy compound lifts can help build peak bone mass. PubMed

Reduced Injury Risk via Strength

Stronger athletes tend to be more robust. In collegiate sports, relative back-squat strength (1RM divided by body mass) has been shown to be associated with a lower risk of lower-extremity injuries across a season. PubMed

Enhanced Performance and Function

Squats develop lower-body strength and power, improve trunk stability and help build a foundation for explosive tasks like sprinting, jumping and rapid changes of direction. Biomechanical reviews emphasise how back squats load the hips and knees in a way that closely relates to athletic movement and everyday tasks. PubMed

In short: get your squat right, and you gain a powerful tool for performance, bone health and long-term physical capacity.

Common Squatting Mistakes that Increase Injury Risk

Even experienced lifters can fall into patterns that reduce efficiency and increase joint stress. Below are some of the most frequent issues — and why they matter.

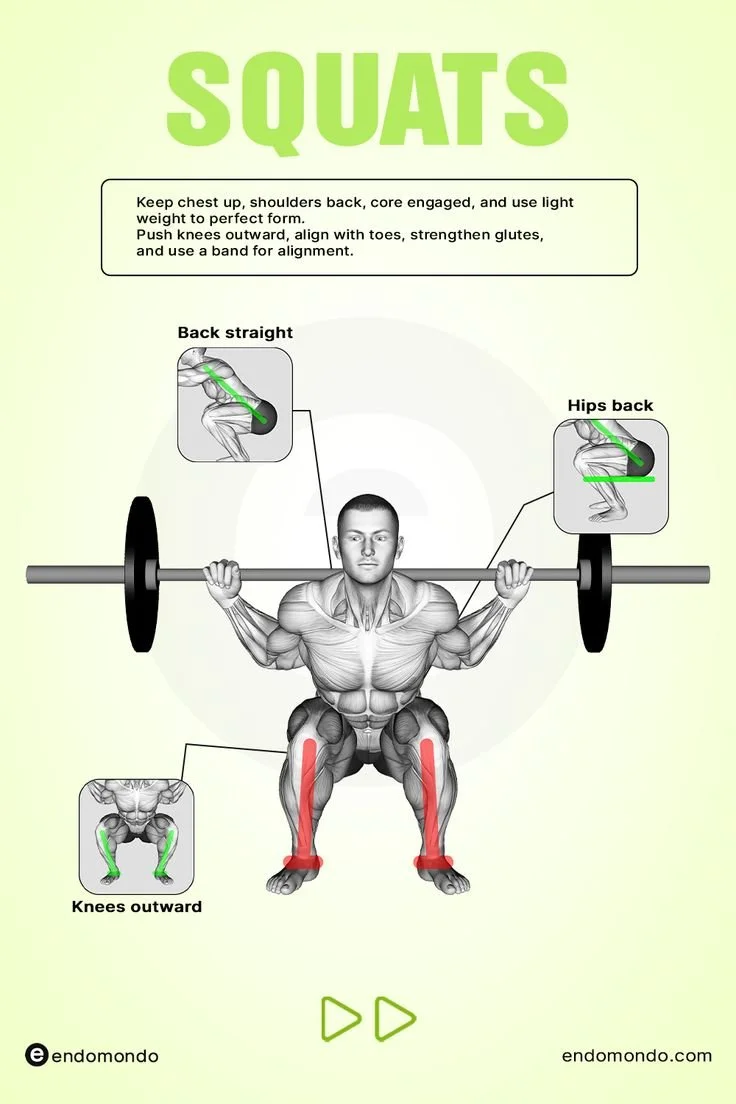

1. Knee Valgus (Knees Caving Inward)

Knee valgus is when the knees collapse inward, especially during the descent or ascent. This pattern is linked to higher risk of knee problems such as patellofemoral pain and ACL injury, particularly in dynamic tasks like jumping and cutting. PubMed

Contributing factors can include weak hip abductors and external rotators, limited ankle dorsiflexion and poor neuromuscular control of the trunk and pelvis. PubMed

In practice:

Think about your knees tracking in line with, or slightly outside, your toes.

“Spread the floor” with your feet to engage glutes and hip stabilisers.

Strengthen hip abductors and external rotators with targeted accessory work.

Address ankle stiffness so your knees don’t have to compensate.

2. The “Butt Wink” (Posterior Pelvic Tilt at Depth)

The “butt wink” describes the pelvis tucking underneath at the bottom of the squat, causing the lower back to round. Some pelvic motion is normal, but excessive lumbar flexion under heavy load can increase shear forces on the spine. PubMed

Common reasons include:

Limited hip flexion or ankle dorsiflexion

Poor control of pelvic position

Insufficient core bracing

A combination of mobility work, better bracing and adjusting stance or depth can usually reduce excessive rounding.

3. Misapplying the “Knees Over Toes” Cue

You’ve probably heard “never let your knees go past your toes.” While it might be useful in some rehab situations, applying it universally is not supported by current evidence.

A classic study found that when forward knee travel was restricted in the squat, knee torque decreased — but hip torque increased by over 1000%, shifting more load to the hips and lower back. PubMed

For many lifters — especially those with longer femurs — some degree of knees-over-toes is both natural and necessary to keep balance and bar path efficient.

The better rule: allow controlled forward knee travel, as long as the knees stay aligned with the feet and don’t cave inward.

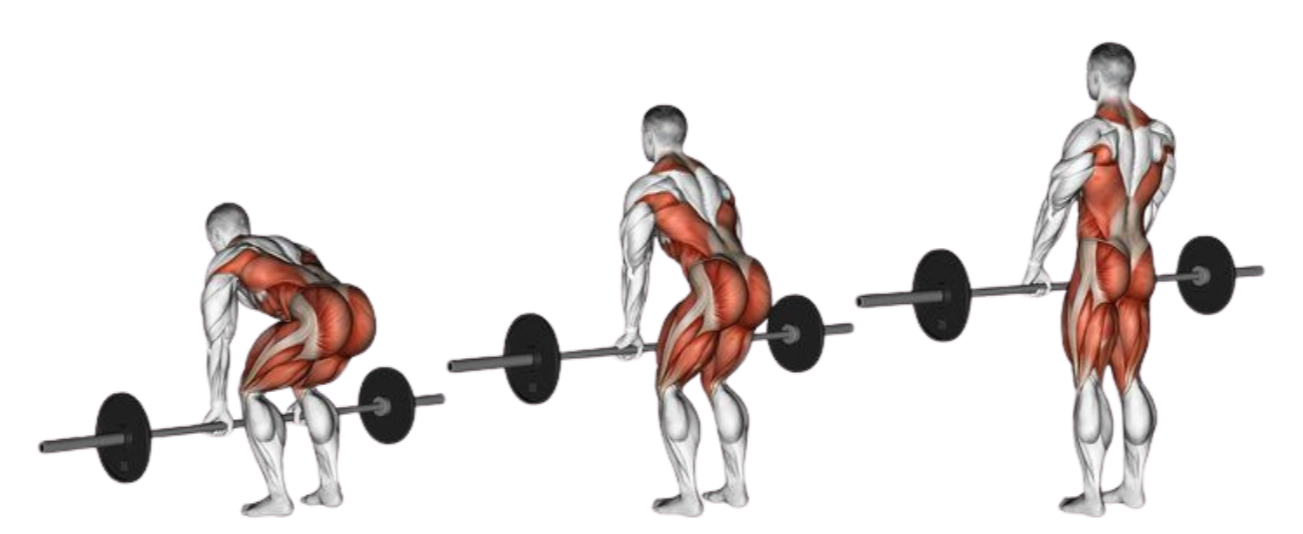

4. Rising with Hips First (“Good Morning Squat”)

In this pattern, the hips shoot up faster than the chest on the way out of the hole, turning the squat into more of a loaded good morning. That increases spinal loading and reduces the contribution of the quads. PubMed

It often reflects weak quadriceps, overly hip-dominant strategy, or poor coordination between knees and hips.

5. Poor Foot Pressure and Balance

Losing balance — rocking back onto the heels or forward onto the toes — can shift stress to the knees, ankles and lower back. Limited ankle dorsiflexion has been linked with altered squat mechanics and compensatory trunk lean. PubMed

A simple rule: maintain a “tripod” foot — big toe, small toe and heel all firmly connected to the floor.

6. Inadequate or Excessive Squat Depth

Squatting high (far above parallel) can limit strength development through full range. Forcing extreme depth when you lack mobility or control can cause compensations such as lumbar rounding or knee collapse. Biomechanical reviews show that as depth increases, joint moments at the hips and knees change substantially, which can be productive or problematic depending on control and context. PubMed

Depth should be based on what you can control with good alignment — not just on arbitrary standards.

7. Poor Breathing and Bracing

Without effective bracing, the spine becomes the weak link in the chain. Proper breathing and bracing strategies — creating intra-abdominal pressure and a rigid torso — increase spinal stiffness and improve load tolerance under heavy squats. PubMed

Many lifters use a controlled Valsalva manoeuvre (brief breath-hold) during heavier attempts; this should be learned gradually and used appropriately.

8. Rushing the Movement (or Moving Too Slowly)

“Dive-bombing” into the bottom position can cause you to lose tension and control, especially under heavy load. On the flip side, moving excessively slowly may fatigue you before you reach the sticking point. Kinematic studies show that load and movement speed interact to influence joint torques and muscle demands. PubMed

Aim for a controlled yet decisive tempo: smooth descent with tension, and a strong, confident drive out of the hole.

9. Incorrect Bar Position and Upper-Back Tightness

Bar placement (high-bar, low-bar, safety bar) and upper-back tightness significantly influence trunk angle and loading patterns. Comparative research on different bar positions and implements shows changes in muscle activation, trunk inclination and joint torques. PubMed

Regardless of your squat style, you need:

A solid “shelf” for the bar

Squeezed shoulder blades

A stable, tight upper back

If shoulder mobility is limited, options like front squats or safety-bar squats can reduce shoulder stress while still training the lower body effectively.

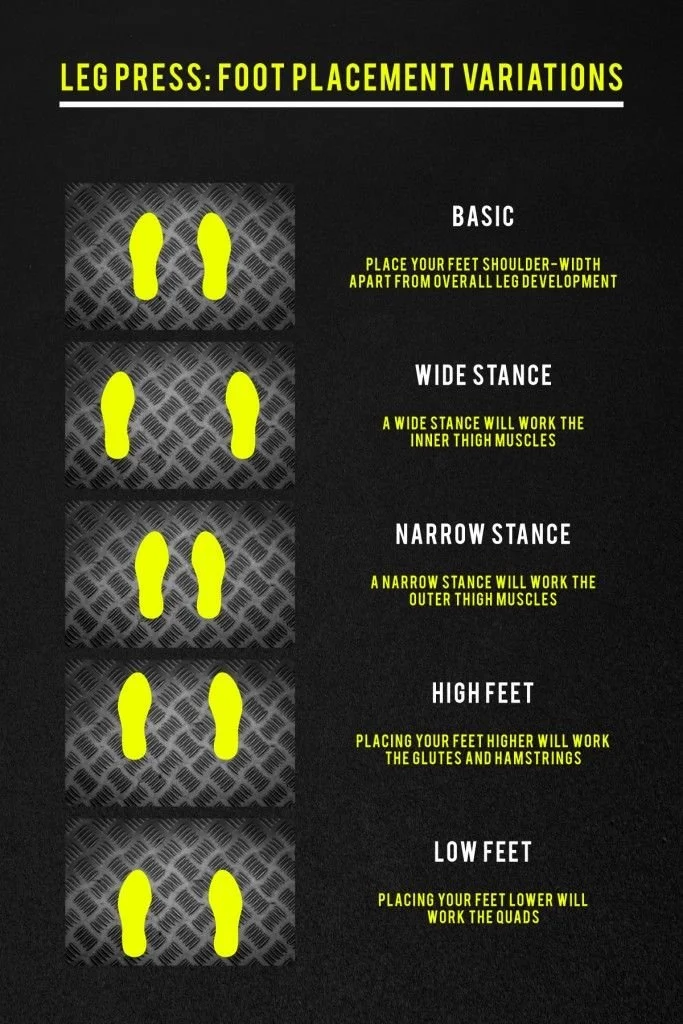

10. Inefficient Stance Width and Toe Angle

Not every lifter should use the same stance. Studies confirm that stance width and foot angle alter hip and knee loading, and experienced lifters often self-select stances that feel more stable and powerful for their anatomy. PubMed

A common starting point is around shoulder-width with toes turned slightly outward (about 15–30°), then adjusting based on comfort, depth and control.

How to Squat Safely: Technique, Progression & Supporting Practices

If you want to maximise the benefits of squatting while minimising risk, a structured approach is essential.

Warm Up Properly

Use light sets, mobility drills and activation work to prepare the hips, knees, ankles and trunk before heavy loading.

Progress Gradually

In strength sports, injury incidence remains low — typically around 1–4 injuries per 1,000 training hours — when training is well planned. PubMed

Avoid aggressive jumps in load. Let your tissues adapt over weeks and months.

Build Supporting Strength

Use accessory exercises for:

Glutes and hamstrings (RDLs, hip thrusts, back extensions)

Quads (front squats, split squats, step-ups)

Core (planks, dead bugs, bird dogs, Pallof presses)

Upper back (rows, face pulls, reverse flyes)

Work on Mobility

Address tight hips, ankles or thoracic spine so you can achieve positions comfortably rather than forcing your body into range it doesn’t own.

Prioritise Technique Over Ego

Use lighter loads when learning or refining technique. Filming your squats from the side and front can reveal issues you can’t feel in the moment.

Use Squat Variations Strategically

Goblet, front, box, safety-bar, belt and Bulgarian split squats all have roles depending on your structure, history and goals.

When to Seek Professional Guidance

You should strongly consider working with a qualified coach or physiotherapist if:

You’re new to squatting and want to learn solid technique from the start

You experience recurring pain during or after squats

You’re coming back from a knee, hip, or back injury

You’re stuck in a plateau and can’t identify why

You plan to compete or train with very heavy loads regularly

In the UK, look for coaches with credentials from bodies such as the UK Strength and Conditioning Association (UKSCA), British Weightlifting, or internationally recognised organisations like the NSCA. A good practitioner will assess your movement, mobility, history and goals, then tailor your squat approach to you.

Final Thoughts: Respect the Squat — and Your Body

The squat is one of the most valuable exercises you can perform for strength, performance, bone health and overall function. The research consistently supports its benefits when it’s programmed intelligently and performed with good technique.

Squats themselves are not the problem — but loading poor movement patterns, ignoring pain, and rushing progression can be.

Respect the movement, progress patiently, and keep refining your technique. Do that, and the squat will pay you back in strength, resilience and long-term capacity for years to come.

View our Services

Injury Consultation

Our Consultation With Treatment service offers professional physical therapy solutions tailored to your unique needs. 20/30-minute consultation discussing concerns, goal setting, and preferable methods. Followed by a physical assessment,

Treatment personalised treatment plans, and ongoing support to help you achieve optimal physical well-being

Injury Rehabilitation

Our Injury Rehabilitation Sessions are focused on restoring mobility and functionality. Patient-centred approach tailored to get you back to the office or the pitch. The sessions utilise evidence-based techniques and therapist knowledge to provide effective rehabilitation. We create and take you through every step of a personalised treatment plan tailored to your specific end goal, ensuring a swift and successful recovery.

Deep Tissue Massage

Deep Tissue Massage is a highly effective therapeutic service provided by our expert physical therapists. Using targeted, firm pressure, this treatment focuses on relieving chronic muscle tension and knots, promoting improved flexibility, and enhancing overall relaxation. Experience the benefits of our professional deep tissue massage to alleviate pain and restore optimal physical well-being.